12/09/2011

10/06/2011

Jim Strahs

Jim Strahs died in Vermont on October 1. I was lucky enough to perform in a play he co-wrote with Richard Maxwell, called Cowboys & Indians, and perform with him in an early version of The Florida Project by Tory Vazquez.

|

| Jim Strahs in 1982.

I don’t think I knew Jim very well. I wouldn’t say I did if

someone asked. He is among the ten most important writers for me, though. It was in the way he made you keep up with him, the way he

got you to see things that maybe you didn’t want to, at the same time as he

cracked you up.

My first interaction with him was at a party in the loft that a

lot of theater dorks shared, over on Desbrosses street. He leaned over me (not

many people can lean over me) and said, “You’re the guy that married Johanna.”

I said I was. “Smart man,” he barked or croaked, and walked away, saying it

again. “Smart man.” (He was right.)

He hadn’t introduced himself so I had no way of knowing he was the guy who wrote North Atlantic, which, for me, was like an hour and forty-five minutes of perfect time. Maybe that was part of why Jim was such a good match for the Wooster Group – the company has a knack for controlling time in their shows. Jim even said that about Ron Vawter when we were talking once at a Cowboys & Indians rehearsal. “Ronny controlled time,” he said. And of course I had never thought to put it that simply when I tried to explain to people how Vawter had changed my understanding of what live performance could be.

A year or two after Cowboys

& Indians, I would run into Jim every so often, at Amalgamated Bank on

Union Square. I was putting pay in the bank, and he was running an errand

for his gig doing payroll, I think for a labor union. He genuinely liked that job, in a non-condescending, almost

guileless way. It was solid work; he had benefits; he was getting his

teeth fixed.

Those conversations, usually about five minutes each, about

doing payroll and writing plays, were moments I looked forward to because there

was never any guesswork—he was always on the level. And he’d probably never have

used that phrase. He’d have been able to put it more meaningfully, without

doctoring it up. What I mean is that his incredible tone of voice, combined

with what he said, and the way he ranged, physically, made everything that came

from him truer than if anyone else had said it.

I realized the other day that since Jim left New York for Vermont,

and largely checked out of the scene, I had kept a mental image of him up

there, which I would wordlessly check in with every so often. I

thought of him going through old notebooks, sitting in a small place, maybe

depressed, maybe just quiet, writing when the urge hit him, looking out the

window a lot, tracking through notebooks from years ago and thinking about what

of it was worth keeping. Because it's how I knew him, I always see him in his long leather coat, doing

all these things.

I keep him there because it helps me clear away my own

bullshit, sit down again and just put down some words.

It’s easy to fall into clichés talking about a dead

colleague or friend. It’s probably even easier when it’s someone you think of

as an unconscious mentor. God forbid a kind of artistic role model. To get it

out of the way: Jim had so much integrity. There was none of the separation

between him and his language – the body and the word – that happens so

regularly when we try to make a living out of our compulsions or callings. Jim

didn’t bother with that, for all the right reasons.

For people who knew him or had an experience with his writing,

the force of it is titanic. If he kept his focus narrow, it was because each

sentence bore the weight of at least a hundred pounds of reckoning.

I am puzzled as to why Jim’s work has not had more reach. I

think the failing is everyone else’s but his. I keep wondering why there

couldn’t be more room in a larger world for someone like him – someone who’s

never going to glad-hand or kowtow, who’s just going to get each moment. What

do we say to this silence now?

|

Labels:

Jim Strahs,

Obituary,

Playwright,

Theater,

Wooster Group

9/27/2011

Occupiers

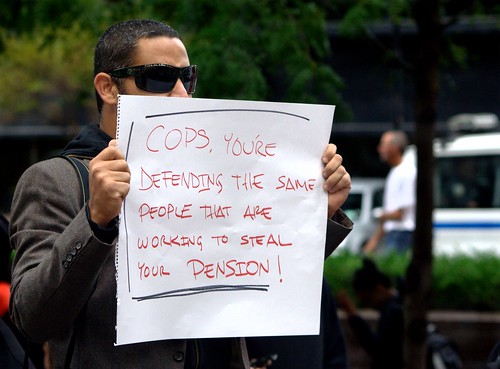

Part of what moves me so much about the Occupy Wall Street protests and their offshoots is the earnestness. Part of it is the times we live in seeming to demand direct action, part of it is the commitment to non-violence and to thoughtful communication.

But probably the biggest part of it for me is semantic.

The protest movement has failed in the last 20 years, in part, because it has harnessed a rhetoric made up solely of demands and statements that are factually incorrect, or at least are arguable. NOT IN OUR NAME always rubbed me the wrong way because it wasn't true. Our government did go to war in our name. The soldiers doing the killing and dying were our family members and friends; they were absolutely fighting in our name. The 2000 election was stolen by the right and relinquished by the center in our name. What has been so painful is that our name has been used to perpetrate unspeakable wrongs.

The tenor of that language cut me off because it made the ineffectual nature of the protests that much more palpable. The more people said it was not in their name, the more was done in our names. And so at a certain point, why bother. And that manner of speaking, that kind of poster, leaves no room for wonder or debate, sorrow or hope. It's just a command - you're either in or you're out - and that is not the world I want to make.

When I look at the signs, the blogs and the interviews with Occupy Wall Street and its offshoots, I'm seeing and reading and hearing something else. "We are the 99%." All of a sudden I can decide whether or not I'm part of that percentage! Thanks for the invite! "I can't afford a lobbyist." Neither can I! I keep hearing stories of the way strangers are welcomed at protest sites, that non-violence is championed, and that people in the movement are clear about what they don't know, as much as what they believe.

It's hard to admit that maybe it's just an aesthetic shift that has brought me into this. Maybe I really am that shallow. (Though I know I've been slowly becoming more radicalized anyway). But as someone who is obsessed with the way we talk to each other, as much as what we say, I think what's happening here, how it's happening, speaks to something deeper in the grain of this activism.

Occupy Chicago on non-violence.

Chris Hedges.

Labels:

Language,

non-violence.,

Occupy Chicago,

Occupy Wall Street,

Protest,

Rhetoric,

Semantics

9/25/2011

Labor Day in Urbana, IL

9/21/2011

How does a city evolve?

I was lucky enough to spend the weekend in Detroit. Among

other activities, I got to hang out and work with some incredible artists who’d

just been awarded fellowships from The Kresge Foundation, I had beers with a

couple radical priests, one my father-in-law, I drove through the always

mystifying cityscape, and I talked to Grace Lee Boggs, an amazing 96 year-old activist

and writer who has been inspiring me a lot lately.

One of the through-lines over the weekend was the sense that

Detroit is in the midst of a set of changes, the outcome of which no one can

predict. It was sort of shocking to hear folks who’d been there for 30, 40 or

even 60 years, who’d witnessed many cycles of ill-conceived urban renewal and thwarted

hopes for their hometown, tell me that things might work out for the better

this time. Or they may just continue to collapse.

Detroit is undergoing what Boggs calls a “dual power

structure.” There are small enclaves that are basically taking on everything

from farming to policing to education, as the city becomes less and less able

to provide those services in our declining economy. At the same time there is a

lot of speculation going on by real estate developers and politicians about the

possibilities of a creativity-led rebound for the city, fed by a combination of

cheap housing, fine architecture, and what locals sometimes refer to “ruin-porn” (the

fetishization of decay into an attractive commodity).

Even Boggs, an activist in Detroit for nearly 60 years, a

PhD, one of the most forward-thinking writers I have ever read on the subject

of political change, when I asked her what she would imagine for the city going

forward, said, “I have no idea. It is impossible to predict.”

Perhaps what we are witnessing is a tension between Detroit

as the city American capital has left behind, and as a city that

is forming the next iteration of whatever a new predicament could become.

Meaning, five or ten years from now, perhaps it will again be impoverished and

neglected, its population again abandoned by

corporate and government misuse and disorder. Perhaps it will embody a new

communitarian movement. Perhaps it will be gentrified into a mall-like version

of its former self. Ruin porn with fairtrade lattes.

Maybe all these potentialities will exist there. It will be

the city with the hip gallery district, rehabbed Victorian homes and Niman

Ranch barbecue, next to the inventive and inclusive projects that Detroit

Summer has undertaken, next to the $1,000 homes complete with available farm

plot, where you just have to provide your own electrical wires, neighborhood

patrol, home school and art event.

Like the residents I talked to, I find myself hopeful and

harrowed at the same time. It is possible there in a way few cities could

imagine: the footprint of Detroit is the same size as Manhattan, San Francisco

and Boston combined; the population is only 720,000. So there’s a lot of space.

I like to think it’s not too late for an alternative strategy to

emerge. I like to think people taking the shortcomings of the existing power

structure into their own hands could actually amount to a real and profound

change, person by person, in a city that is struggling and growing and

celebrating itself anew.

Further reading

Bill Wylie-Kellerman

The Boggs Center

Detroit Summer

Invincible

Further reading

Bill Wylie-Kellerman

The Boggs Center

Detroit Summer

Invincible

9/08/2011

Contemporary National Politics Today

So, the right are basically two-year-olds throwing tantrums, pulling everything off the shelves, breaking all the dishes and hurting themselves. They are tearing apart the house. The Democrats' response is to stand in alternate between saying "don't do that," and, "Look at us! We're not that mad! We're reasonable!" Meanwhile the kids have gotten ahold of the frying pans and are smashing out the windows, flooding the basement, pissing on the art. Maybe our job is to keep them out of danger, remind them that we love them, and let them spin themselves out until they take a good long nap.

9/02/2011

Prose poem?

I am cleaning out files and folders. I came across this. Is it enough to stand alone as a prose poem? Please answer in the comments below:

****

" She could tell by his breathing what the dream was about. He had told her enough times after waking and she could often remember the particular qualities that signified running, or loving or flight. She had catalogued his subconscious before he fell asleep. And she was keeping it a secret from him – as far as he knew she was asleep beside him. She came from a long line of insomniacs, worriers, night owls, minds that never took vacations. She didn’t love him any less for it; it gave her a certain power over him, about which only she was clued in. This was the beginning of their real intimacy." - November 2009.

****

" She could tell by his breathing what the dream was about. He had told her enough times after waking and she could often remember the particular qualities that signified running, or loving or flight. She had catalogued his subconscious before he fell asleep. And she was keeping it a secret from him – as far as he knew she was asleep beside him. She came from a long line of insomniacs, worriers, night owls, minds that never took vacations. She didn’t love him any less for it; it gave her a certain power over him, about which only she was clued in. This was the beginning of their real intimacy." - November 2009.

8/10/2011

Incremental Fiction (Pretending To Wake Up), part 4

***

One winter, around that time, I am home for a holiday visit, walking around on a cold night, just after last call, and I stop by Curly’s, a diner open until four so drunks can dry up after last call. Curly’s is a place where I don’t expect to see anyone I know, where I go to get warm and avoid everyone.

At first I don’t recognize the bloated guy behind the grill with the apron around his waist and the towel over his shoulder. He’s been kicked out of The Replacements for doing too many drugs, which is like to being kicked out of a school of fish for being too wet. He looks ruined now.

When I realize who it is, I say “Bob Stinson?” and he looks at me a little suspiciously.

“Do I know you?” he asks.

I tell him no but I used to see him play a lot, and I miss him in the band. He smiles and stares at me for a long time, unblinking. A few months later he’ll be dead; so many years of abuse will have made it impossible for his organs to continue functioning.

Before I leave, Bob gives me a napkin with his autograph scrawled on it. “Don’t tell anybody I’m here,” he mumbles. The sky is starting to lighten faintly with that dull gray glow, and I know this means soon I will have to go home and pretend to wake up.

The end.

7/22/2011

Incremental Fiction (Pretending To Wake Up), part 3

We both go to New York for college in '87. James studies history for a semester but drops out so he can “model” and “play bass” full-time, which means just enough to score. Over the next couple years I see him less but I hear stories—he’s back home, in a band called That Darn Cat who all live together in a house on Harriet, where they noodle with feedback and do drugs. Now he’s back in New York. Now he’s gotten his model girlfriend pregnant and they both still use. He seems embarrassed around me, overcompensating with meanness; after awhile I start to let the friendship slide away.

**

When I go back to Minneapolis on holiday breaks, I walk and walk and walk. Unconsciously, I think I’m looking for the energy that saved me, I’m looking for Goofy’s Upper Deck but it’s closed; The Replacements are on a major label. The scene knows itself and some of the energy has dissipated. I want this place to freeze itself in time so I can come back and taste that desperation and then leave again when it’s convenient. Why is my hometown smoothing out its edges? Why is it growing up?

**

This is the last time I see James: 1992, we are both twenty-five and he’s a full-fledged junkie. He shows up at my door one evening and takes me to his apartment, a former storefront on Ludlow Street, where the lights have been turned off by Con-Edison and a naked man nods on a naked mattress with blood from a bad puncture drying on his forearm. Half feral, rib-thin cats mewl and nose at empty cans of Friskies. (A few years later I’ll unwittingly walk into the same space, now a clothing store, to buy my wife an $80 sweater for Christmas, made from the salvaged scraps of vintage cashmere.)

James shows me where he’s cut a little piece of plaster out of the wall, behind which he’s hidden anything of value: a picture of his baby girl he doesn’t have visitation rights to; a few dollars; a mix tape I’d made him for our road trip to New Orleans. I’ve given up on him and he’s saving this?

We walk around the city for a few hours and he tells me he is down to a couple bags in the morning and a couple to get to sleep. I don’t know what this means but it doesn’t sound reassuring. He says he doesn’t want to end up one of those guys he’s seen at meetings, telling everyone what a good day it was because he was able to sit down in front of a TV show without wanting to claw out his eyes. He has a junkie’s remarkable ability to slip from coherence to abject superstition in an instant. “Did you know,” he asks me as we stop somewhere for a drink, “that they did a study of addicts and over two-thirds are Scorpios?”

**

7/15/2011

Incremental Fiction, ("Pretending to Wake up"), part 2

James and I start going to all-ages shows tucked away in sweaty holes by the University, five-band-five-dollar nights of half in-tune guitars and screamed rants distorted through a cheap sound system. The first is headlined by Husker Du, and it is terrifying. Bob Mould screams, red-faced, and grinds away at a Flying-V guitar; he has a paunch, bad skin, big black shorts and boots. Grant Hart looks like a hairy caveman bashing his drums. It sounds like a car accident I want to get killed in. The bands sweat and careen for us and we do the same in response. Our favorite player is Bob Stinson, guitarist for The Replacements, who shows up onstage wearing only an adult diaper or a thrift-store prom dress. He gets so drunk before gigs that a roadie has to help him strap on his guitar. He is equally legendary in Minneapolis for his brilliant solos and his ongoing calamity of a life. What he plays is what I hear when I can’t sleep.

**

James’s and my friendship expands to include nights at Embers’, the only all-night restaurant within walking distance from our houses, a tinted glass diner populated by post-bar drunks, staffed by a waitress with a wandering eye. We spread our homework on the table to look reputable, drink coffee and talk about bands. When the sky starts to glow, predawn, we sneak back home and pretend to wake up for school.

On the bus one day, James mentions heroin to me. He’s tried it with the motorcycle boys he’s gotten to know, and asks me if I want to do it, too. He says it erases all his desire and anxiety, he says it’s like the feeling after sex. Still antsy all the time, and awkward in my own skin, I’m thinking this sounds like exactly what I need, even if the idea of sticking a needle in my arm is scary, and even if I don't know what sex feels like, though of course I nod my head. I tell him okay, but at the appointed time I chicken out. We don’t discuss it after that.

7/08/2011

Incremental Fiction ("Pretending to Wake Up"), part 1

It’s 1982, I am in seventh grade and I can’t sleep. I’m involuntarily replaying the previous day’s events in my head: schoolmates’ little insults; subtle rebukes by girls I’d like to kiss; what I should have told the math teacher who gave me a C. I’m tossing and turning, fumbling through Minneapolis’s numbing selection of late-night radio in my basement room: Pop, Country, Muzak, Classical, news. At some point during the night, I land for the first time on KFAI, a local station, and a show called Rock of Rages. The reception is spotty, but two songs come through clear enough: “Blue Spark,” by X and “Kids Don’t Follow” by The Replacements. The guitar is fuzzier, the voices are desperate, the beats race. Is it possible that The Replacements actually come from my hometown? Until now I’ve known this city to be a place that is white, still and cold, where no one ever quite approves, where you are always too loud, too quiet, too weird or too normal.

**

There’s one kid in South Minneapolis, James Frierson, who will hang out with me if everyone else he knows is busy. We ride the bus together up Lake Street to the Hi-Lake Mall, past used car lots and the Scandia Bakery, the bank and American Rug Laundry and Embers’ Grill. When we get there we pace the aisles of Target and play with the walkie-talkies at Radio Shack until the manager tells us to stop.

Already James is so good looking that when he walks to the back of the bus all the women and some of the men turn to watch him pass. Sometimes I rush to sit down first so I can see it happen. He is apple-cheeked, blue-eyed, soft-voiced and big-boned. I am gangly, buck-toothed, uncoordinated. We are a perfect odd couple.

James had come back from spring break a few weeks back, having traded the Izod shirts and khakis we all wore for something else. His t-shirt was ripped, he had a bandana around his neck, he wore tight black jeans and his hair was spiky. “It’s not Preppy anymore,” he informed me with disdain, “It’s Punk now.” He was so sure of this fact, and it was so clear that whatever punk was, I was not it, that I knew it was just a matter of time before he’d ditch me for good, and only hang out with all the other kids who had always known it was punk the whole time.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)