Jim Strahs died in Vermont on October 1. I was lucky enough to perform in a play he co-wrote with Richard Maxwell, called Cowboys & Indians, and perform with him in an early version of The Florida Project by Tory Vazquez.

|

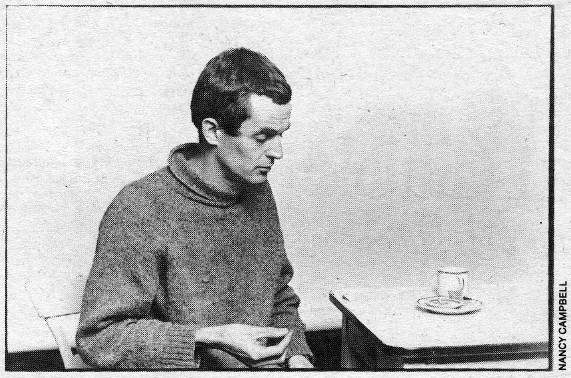

| Jim Strahs in 1982.

I don’t think I knew Jim very well. I wouldn’t say I did if

someone asked. He is among the ten most important writers for me, though. It was in the way he made you keep up with him, the way he

got you to see things that maybe you didn’t want to, at the same time as he

cracked you up.

My first interaction with him was at a party in the loft that a

lot of theater dorks shared, over on Desbrosses street. He leaned over me (not

many people can lean over me) and said, “You’re the guy that married Johanna.”

I said I was. “Smart man,” he barked or croaked, and walked away, saying it

again. “Smart man.” (He was right.)

He hadn’t introduced himself so I had no way of knowing he was the guy who wrote North Atlantic, which, for me, was like an hour and forty-five minutes of perfect time. Maybe that was part of why Jim was such a good match for the Wooster Group – the company has a knack for controlling time in their shows. Jim even said that about Ron Vawter when we were talking once at a Cowboys & Indians rehearsal. “Ronny controlled time,” he said. And of course I had never thought to put it that simply when I tried to explain to people how Vawter had changed my understanding of what live performance could be.

A year or two after Cowboys

& Indians, I would run into Jim every so often, at Amalgamated Bank on

Union Square. I was putting pay in the bank, and he was running an errand

for his gig doing payroll, I think for a labor union. He genuinely liked that job, in a non-condescending, almost

guileless way. It was solid work; he had benefits; he was getting his

teeth fixed.

Those conversations, usually about five minutes each, about

doing payroll and writing plays, were moments I looked forward to because there

was never any guesswork—he was always on the level. And he’d probably never have

used that phrase. He’d have been able to put it more meaningfully, without

doctoring it up. What I mean is that his incredible tone of voice, combined

with what he said, and the way he ranged, physically, made everything that came

from him truer than if anyone else had said it.

I realized the other day that since Jim left New York for Vermont,

and largely checked out of the scene, I had kept a mental image of him up

there, which I would wordlessly check in with every so often. I

thought of him going through old notebooks, sitting in a small place, maybe

depressed, maybe just quiet, writing when the urge hit him, looking out the

window a lot, tracking through notebooks from years ago and thinking about what

of it was worth keeping. Because it's how I knew him, I always see him in his long leather coat, doing

all these things.

I keep him there because it helps me clear away my own

bullshit, sit down again and just put down some words.

It’s easy to fall into clichés talking about a dead

colleague or friend. It’s probably even easier when it’s someone you think of

as an unconscious mentor. God forbid a kind of artistic role model. To get it

out of the way: Jim had so much integrity. There was none of the separation

between him and his language – the body and the word – that happens so

regularly when we try to make a living out of our compulsions or callings. Jim

didn’t bother with that, for all the right reasons.

For people who knew him or had an experience with his writing,

the force of it is titanic. If he kept his focus narrow, it was because each

sentence bore the weight of at least a hundred pounds of reckoning.

I am puzzled as to why Jim’s work has not had more reach. I

think the failing is everyone else’s but his. I keep wondering why there

couldn’t be more room in a larger world for someone like him – someone who’s

never going to glad-hand or kowtow, who’s just going to get each moment. What

do we say to this silence now?

|